Introduction

You're 20 minutes into a system outage. Your IT team is deep in diagnostics, trying to figure out if it's the payment processor, the core banking platform, or something upstream. Meanwhile, your Communications Director is fielding angry calls from branch managers who need to tell customers something. Anything.

But IT can't give a clear answer yet. Communications doesn't want to say the wrong thing. So customers get conflicting information, employees improvise their own explanations, and what could've been a controlled response turns into a reputation problem. This scenario plays out hundreds of times a day across organizations with multiple locations. The gap between technical response and stakeholder communication isn't just inconvenient. It's expensive.

The Structural Problem: Two Teams, Two Priorities

IT operations and communications departments measure success differently. IT cares about mean time to resolution (MTTR) and system uptime. Communications cares about message consistency and stakeholder trust. During an incident, those priorities collide.

IT wants to solve the problem before talking about it. Communications needs to say something now, even if the full picture isn't clear. Add in competing workflows, different terminology, and separate reporting structures, and you get what researchers call 'structural silos.' These aren't personality conflicts. They're baked into how departments are built.

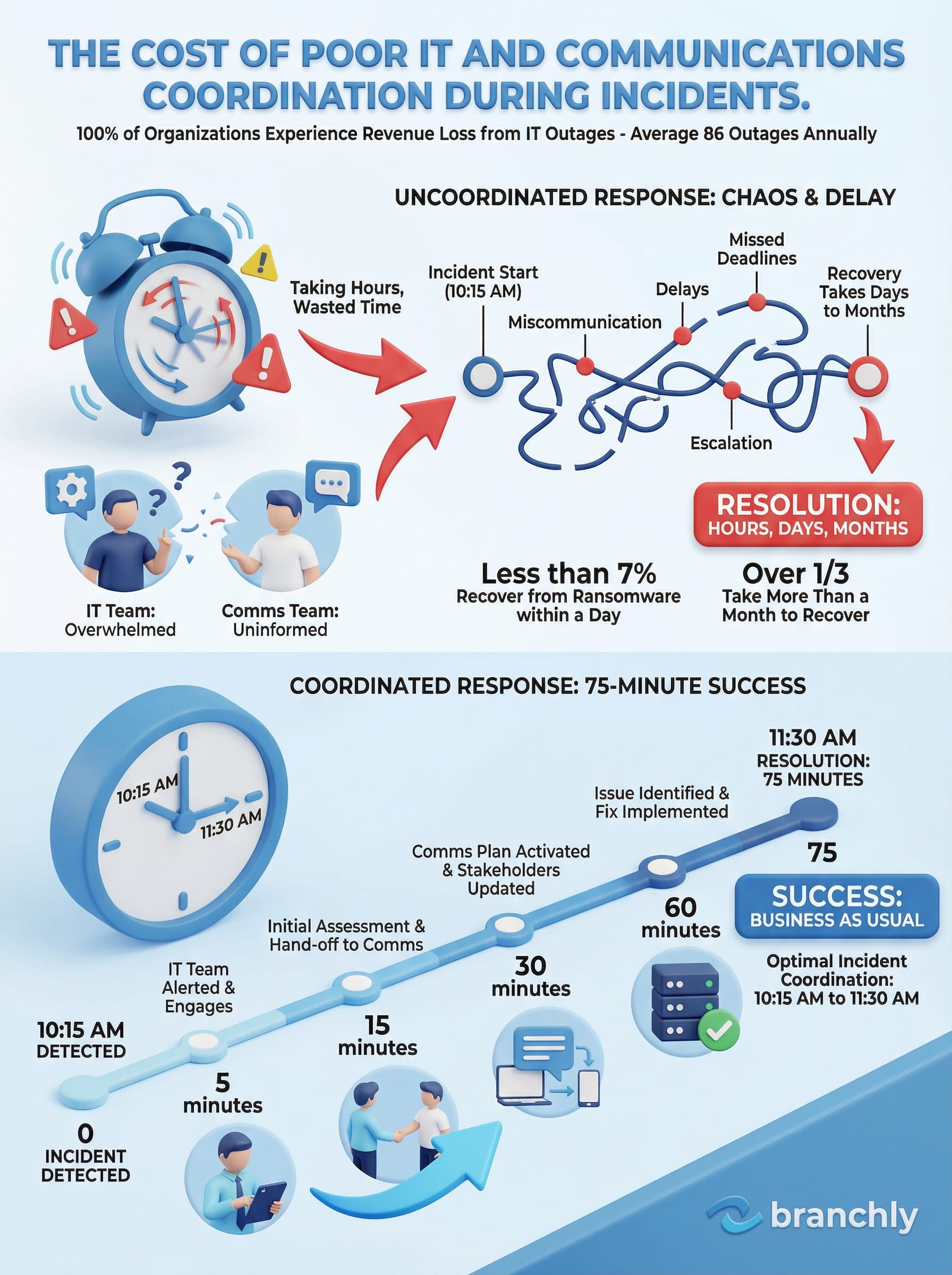

The cost is real. A 2025 survey found that 100% of organizations experienced revenue loss due to IT outages in the previous year, with an average of 86 outages annually. Many of those losses weren't just from downtime itself, but from poor coordination that stretched recovery times and damaged customer relationships.

Quick Win

Create a two-sentence template that IT can fill in during the first 15 minutes of any outage: 'We are aware of [specific system] issues affecting [specific functions]. We expect to have more information by [specific time].' This gives Communications something accurate to work with immediately.

What Happens When Roles Aren't Clear

During Hurricane Katrina, multiple agencies conducted redundant damage assessments because no one had defined who owned which geographic area or asset type. They wasted days duplicating work while people waited for help.

The same dynamic plays out in business incidents, just with lower stakes. Without predefined accountability, teams hesitate to act or escalate unnecessarily. Someone from IT might notify Communications too late because they thought the issue would resolve quickly. Communications might send a message without technical review because they didn't know who to loop in.

The result: delayed responses, mixed messages to customers, and post-incident finger-pointing. Decision-making slows to a crawl because everyone's checking with everyone else, or no one's checking at all.

Real Cost

Less than 7% of organizations can recover from ransomware within a day. Over a third take more than a month, often due to poor coordination between IT, security, and business units during the response.

The RACI Framework: Who Does What

The RACI model (Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, Informed) solves the role ambiguity problem by assigning clear ownership to every task in your incident response. It's not complicated, but it requires you to make decisions ahead of time about who does what.

Here's how it works during a system outage: IT Operations is Responsible for diagnosing and fixing the technical issue. The IT Director is Accountable (owns the outcome). Communications is Consulted for message drafting. Branch managers and customer service are Informed of status updates.

The magic is in separating Responsible from Accountable. The person doing the work (Responsible) isn't always the person who answers for the result (Accountable). This prevents bottlenecks where a senior leader has to approve every small decision.

For cross-functional handoffs, RACI makes the relay points explicit. When IT moves from 'investigating' to 'implementing fix,' that's the trigger for Communications to shift from 'drafting holding statement' to 'preparing resolution message.' No guessing.

The DACI Alternative: When Speed Matters Most

DACI (Driver, Approver, Contributors, Informed) is RACI's faster cousin. It works better for time-sensitive decisions where you can't afford long consultation loops.

The Driver owns the decision-making process and pulls in Contributors as needed. The Approver has final sign-off. Everyone else is Informed after the fact. This model shines during active crises when you need one person driving the response, not a committee.

For example: during a data breach, your Security Lead is the Driver. They decide which forensic firm to hire, what systems to isolate, and when to notify regulators. The CIO is the Approver for major decisions (like taking production systems offline). IT, Legal, and Communications are Contributors who provide input. The Board is Informed.

The key difference from RACI: the Driver can make calls without checking every box. That speed matters when you're racing regulatory notification deadlines or trying to contain an active threat.

When to Use Which

Use RACI for planned responses and recurring incidents where you want broad input. Use DACI for fast-moving crises where centralized decision-making prevents chaos. Some organizations map both: RACI for the overall incident response plan, DACI for specific high-stakes decisions within it.

Breaking Down the Communication Barriers

Even with clear roles, IT and Communications often speak different languages. IT talks about 'service degradation' and 'failover procedures.' Communications needs to translate that into 'some transactions may be slower than normal' and 'we're switching to backup systems.'

This translation gap causes two problems. First, it slows everything down. Communications can't draft accurate messages until they decode the technical update. Second, it introduces errors. A misunderstood technical detail becomes a wrong promise to customers.

The fix is shared terminology and standardized status templates. Create a simple status lexicon that both teams use: 'Investigating' means we know something's wrong but haven't identified the cause. 'Identified' means we know what's broken. 'Monitoring' means the fix is in place and we're watching for issues. 'Resolved' means it's over.

Pair each status with a pre-written message template. When IT updates the status to 'Identified,' Communications automatically knows which template to use and just fills in the specifics. No back-and-forth required.

Building the Feedback Loop

After every incident, conduct a joint post-mortem with both IT and Communications in the room. Don't just review what broke technically. Review the coordination.

Ask specific questions: When did IT first notify Communications? Was that soon enough? Did Communications have the information they needed to draft accurate messages? Were there any points where the teams were waiting on each other? Did customers or employees get conflicting information from different sources?

Track these handoff metrics over time. If Communications consistently says they needed information sooner, that's a signal to adjust notification triggers. If IT says they were pulled into message review too often for minor updates, maybe Communications needs more pre-approved language to work with.

This feedback loop turns incidents into training opportunities. Your response gets tighter with each iteration.

Warning Sign

If your post-incident reviews only happen when something goes badly wrong, you're missing 90% of the learning opportunities. Brief after-action reviews following minor incidents catch coordination problems before they matter.

The Role of Leadership in Cross-Functional Response

Department silos don't fix themselves. Leadership has to make cross-functional coordination a priority, not an afterthought.

That means aligning incentives. If IT is measured purely on uptime and Communications is measured purely on message speed, they'll keep working in parallel. Add a shared metric: time from incident detection to first accurate customer communication. Now both teams have a reason to coordinate.

Leadership also needs to create psychological safety for these cross-functional relationships. IT won't tell Communications 'I don't know yet' if the culture punishes uncertainty. Communications won't push back on unrealistic timelines if they're seen as not being team players.

Regular joint training helps too. Run tabletop exercises where IT and Communications practice the handoff. Not just what to do, but when to loop each other in and what information the other team needs. Make the muscle memory before the real crisis hits.

Pre-Approved Messages: The Bridge Between Speed and Accuracy

One of the biggest friction points is the approval process. Communications drafts a message, sends it to IT for technical review, IT suggests changes, Legal needs to see it, by the time it's approved the situation has changed.

Pre-approved message templates solve this. Work with IT, Legal, and Communications during calm times to draft template messages for common scenarios: payment system outage, website downtime, data security incident, facility closure.

Get all the approvals upfront. Legal signs off on the language. IT confirms the technical descriptions are accurate. Communications verifies it matches your brand voice and reading level. Now, during an actual incident, Communications just fills in the blanks (time, location, specific system) and hits send. No approval loop required.

This approach cuts message delivery time from hours to minutes. It also removes the panic-writing problem. Nobody's trying to craft perfect language while customers are calling angry.

Template Types You Need

Build three versions of each template: initial notification (we're aware of the issue), progress update (we're working on it, here's what we know), and resolution (it's fixed, here's what happened). Most incidents only need these three messages.

Technology That Connects Instead of Complicates

The wrong technology makes coordination worse. If IT uses one incident tracking system, Communications uses another, and everyone else is working from email and phone calls, you've just added more confusion.

Effective incident response needs a single source of truth. When IT updates the incident status, Communications sees it immediately. When Communications sends a message, IT knows what was communicated and to whom. When a branch manager marks a task complete, everyone tracking the response sees the update.

This doesn't mean one department has to adopt the other's tools. It means the tools need to talk to each other, or you need a coordination layer that sits above both. Something where the incident status, task assignments, and communication log all live in one place that both teams can access.

The real test: can someone who wasn't involved in the response look at your system a week later and reconstruct exactly what happened, when, and who did what? If the answer is no, your tools aren't doing their job.

What Good Coordination Actually Looks Like

Here's what a well-coordinated incident response feels like: Your payment system goes down at 10:15 AM. By 10:18, IT has confirmed the issue and updated the incident status to 'Investigating.' That status change automatically triggers a notification to Communications.

Communications pulls up the pre-approved 'Payment System Outage - Initial' template, fills in the time and affected locations, and sends it to branch managers by 10:22. Customers start seeing consistent messaging within five minutes.

By 10:45, IT has identified the cause and switched to backup systems. They update the status to 'Implementing Fix' and add an estimated resolution time. Communications sees the update immediately and sends the progress message.

At 11:30, systems are restored. IT changes the status to 'Resolved.' Communications sends the final message. By noon, you're in the post-incident review documenting what worked and what didn't.

Total time from incident to resolution communication: 75 minutes. No one panicked. No one sent conflicting information. Both teams knew exactly what their role was and when to hand off to the other.

Summary

The gap between IT operations and communications isn't a people problem. It's a systems problem. Different priorities, unclear roles, and missing handoff protocols turn manageable incidents into coordination failures. But the fix is straightforward: define roles using RACI or DACI frameworks, build pre-approved message templates, create shared terminology, and give both teams a single source of truth to work from. Most organizations can implement these changes in weeks, not months. The payoff shows up immediately in faster response times, more accurate communications, and fewer post-incident surprises. Your next outage will happen. The question is whether your IT and Communications teams will be working together or just working at the same time.

Key Things to Remember

- ✓IT and Communications fail to coordinate during incidents because of structural silos, different success metrics, and unclear decision-making authority.

- ✓RACI (Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, Informed) and DACI (Driver, Approver, Contributors, Informed) frameworks clarify roles and accelerate handoffs.

- ✓Pre-approved message templates eliminate approval delays and ensure accurate, consistent communication during high-pressure incidents.

- ✓Shared terminology and standardized status updates bridge the language gap between technical teams and communicators.

- ✓Joint post-incident reviews and cross-functional training build coordination muscle memory before the next crisis hits.

How Branchly Can Help

Branchly eliminates the coordination gap between IT and Communications by providing a single command center where both teams work from the same real-time information. When IT updates an incident status, Communications instantly sees the change and accesses pre-approved message templates that match the current phase of response. Role assignments using RACI frameworks are built directly into playbooks, so everyone knows who's responsible for technical resolution, who approves customer messages, and when handoffs occur. Pre-vetted communication templates for common incidents (system outages, security events, facility closures) are already approved by Legal and IT, allowing Communications to send accurate messages in minutes instead of hours. Automated logging captures every status change, message sent, and task completed, creating the defensible audit trail you need for post-incident reviews and regulatory reporting. The result: coordinated response that turns hours of back-and-forth into seconds of decisive action.

Citations & References

- [1]

- [2]

- [3]

- [4]

- [5]Cross-Functional Collaboration: The Complete Guide for Agencies | Screendragon screendragon.com View source ↗

- [6]

- [7]

- [8]

- [9]pnnl.gov View source ↗

- [10]

- [11]

- [12]🔐 Incident Response, Business Continuity and Disaster Recovery | Blog | Jean-Baptiste Bres jbbres.com View source ↗

- [13]nist.gov View source ↗